Veronese surface

In mathematics, the Veronese surface is an algebraic surface in five-dimensional projective space, and is realized by the Veronese embedding, the embedding of the projective plane given by the complete linear system of conics. It is named after Giuseppe Veronese (1854–1917). Its generalization to higher dimension is known as the Veronese variety.

The surface admits an embedding in the four-dimensional projective space defined by the projection from a general point in the five-dimensional space. Its general projection to three-dimensional projective space is called a Steiner surface.

Contents |

Definition

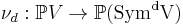

The Veronese surface is a mapping

given by

where ![[x:\cdots]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/194834dd8871e35d172e53f8c415e005.png) denotes homogeneous coordinates. The map

denotes homogeneous coordinates. The map  is known as the Veronese embedding.

is known as the Veronese embedding.

Motivation

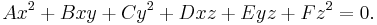

The Veronese surface arises naturally in the study of conics, specifically in formalizing the statement that five points determine a conic. A conic is a degree 2 plane curve, thus defined by an equation:

The pairing between coefficients  and variables

and variables  is linear in coefficients and quadratic in the variables; the Veronese map makes it linear in the coefficients and linear in the monomials. Thus for a fixed point

is linear in coefficients and quadratic in the variables; the Veronese map makes it linear in the coefficients and linear in the monomials. Thus for a fixed point ![[x:y:z],](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/59d91b7d1b0406353107cab6f61aa4a2.png) the condition that a conic contains the point is a linear equation in the coefficients, which formalizes the statement that "passing through a point imposes a linear condition on conics". The subtler statement that "five points in general linear position impose independent linear conditions on conics," and thus define a unique conic (as the intersection of five hyperplanes in 5-space is a point) corresponds to the statement that under the Veronese map, points in general position are mapped to points in general position, which corresponds to the fact that the map is biregular (and thus the image of points are in special position if and only if the points were originally in special position).

the condition that a conic contains the point is a linear equation in the coefficients, which formalizes the statement that "passing through a point imposes a linear condition on conics". The subtler statement that "five points in general linear position impose independent linear conditions on conics," and thus define a unique conic (as the intersection of five hyperplanes in 5-space is a point) corresponds to the statement that under the Veronese map, points in general position are mapped to points in general position, which corresponds to the fact that the map is biregular (and thus the image of points are in special position if and only if the points were originally in special position).

Veronese map

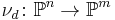

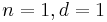

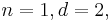

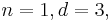

The Veronese map or Veronese variety generalizes this idea to mappings of general degree d in n+1 variables. That is, the Veronese map of degree d is the map

with m given by the multiset coefficient, more familiarly the binomial coefficient, or more elegantly the rising factorial, as:

The map sends ![[x_0:\ldots:x_n]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/6c90f5161b1d2002595c537c07639400.png) to all possible monomials of total degree d, thus the appearance of combinatorial functions; the

to all possible monomials of total degree d, thus the appearance of combinatorial functions; the  and

and  are due to projectivization. The last expression shows that for fixed source dimension n, the target dimension is a polynomial in d of degree n and leading coefficient

are due to projectivization. The last expression shows that for fixed source dimension n, the target dimension is a polynomial in d of degree n and leading coefficient

For low degree,  is the trivial constant map to

is the trivial constant map to  and

and  is the identity map on

is the identity map on  so d is generally taken to be 2 or more.

so d is generally taken to be 2 or more.

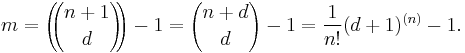

One may define the Veronese map in a coordinate-free way, as

where V is any vector space of finite dimension, and  are its symmetric powers of degree d. This is homogeneous of degree d under scalar multiplication on V, and therefore passes to a mapping on the underlying projective spaces.

are its symmetric powers of degree d. This is homogeneous of degree d under scalar multiplication on V, and therefore passes to a mapping on the underlying projective spaces.

If the vector space V is defined over a field K which does not have characteristic zero, then the definition must be altered to be understood as a mapping to the dual space of polynomials on V. This is because for fields with finite characteristic p, the pth powers of elements of V are not rational normal curves, but are of course a line. (See, for example additive polynomial for a treatment of polynomials over a field of finite characteristic).

Rational normal curve

For  the Veronese variety is known as the rational normal curve, of which the lower-degree examples are familiar.

the Veronese variety is known as the rational normal curve, of which the lower-degree examples are familiar.

- For

the Veronese map is simply the identity map on the projective line.

the Veronese map is simply the identity map on the projective line. - For

the Veronese variety is the standard parabola

the Veronese variety is the standard parabola ![[x^2:xy:y^2],](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/2f3a58838ac7a7f34f12a87e833e0b98.png) in affine coordinates

in affine coordinates

- For

the Veronese variety is the twisted cubic,

the Veronese variety is the twisted cubic, ![[x^3:x^2y:xy^2:y^3],](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/a67e6c2d095172ab943f67c8a7d988d7.png) in affine coordinates

in affine coordinates

Biregular

The image of a variety under the Veronese map is again a variety, rather than simply a constructible set; furthermore, these are isomorphic in the sense that the inverse map exists and is regular – the Veronese map is biregular. More precisely, the images of open sets in the Zariski topology are again open.

Biregularity has a number of important consequences. Most significant is that the image of points in general position under the Veronese map are again in general position, as if the image satisfies some special condition then this may be pulled back to the original point. This shows that "passing through k points in general position" imposes k independent linear conditions on a variety.

This may be used to show that any projective variety is the intersection of a Veronese variety and a linear space, and thus that any projective variety is isomorphic to an intersection of quadrics.

References

- Joe Harris, Algebraic Geometry, A First Course, (1992) Springer-Verlag, New York. ISBN 0-387-97716-3

![\nu: [x:y:z] \mapsto [x^2:y^2:z^2:yz:xz:xy]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/4387353d3b314e206f30369212d336d8.png)